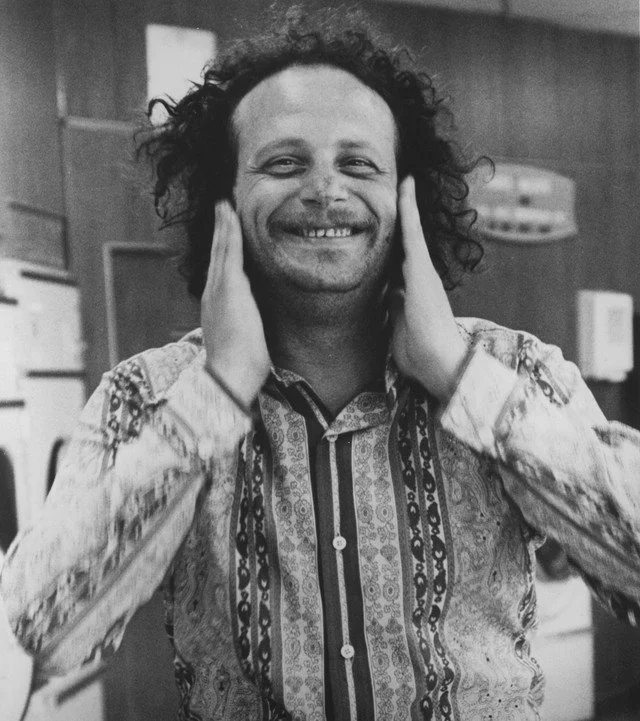

THE OUTSIDERS: Wild Man Fischer was the real thing

by Jeff Cubbison

RateYourMusic defines “outsider music” as “songs and compositions by musicians who are not part of the commercial music industry who write songs that ignore standard musical or lyrical conventions, either because they have no formal training or because they disagree with formal rules.”

Last time on The Outsiders, we looked at Tres & Kitsy, two ten-year-olds who accidentally made a lovely folk record in 1970, then grew up and lived happily ever after. Their story was an anomaly - outsider music as innocence, friendship, and constant sunshine. This time around, we turn to the other end of the spectrum: darkness, instability, and heartbreak. If Tres & Kitsy represent the exception, Wild Man Fischer is the rule - a chaos agent capable of pure, unfiltered outsider expression whose life and music were indistinguishable.

Lawrence “Larry” Fischer was born in Los Angeles in 1944. Growing up just miles from Hollywood but galaxies away from its glitz and glamour, Fischer battled severe mental illness from a young age - later diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic - and spent much of his teenage years in and out of institutions. One of his tamer offenses was getting expelled from Fairfax High for constantly singing in class - no doubt a harbinger of things to come. By the mid-1960s, he had taken to wandering the streets of L.A., singing improvised songs for change, often shouting them at startled passersby. Occasionally, he took his rambling singing act to local talent shows, where he was discovered by R&B singer Solomon Burke, who gave him the nickname “Wild Man” and briefly brought him along on tour. The association didn’t last long though. Soon, Fischer was back in a mental facility, and then back to busking on the streets for change.

However, these spontaneous street performances would become the stuff of local legend. Surreal, funny, fragment-like, and painfully honest, he wasn’t performing irony or avant-garde theatre. He was simply being himself - a man compelled to sing the way others breathe, despite possessing zero formal training or grasp of musical theory.

One day in 1968, the universe aligned in the strangest way possible: Frank Zappa, the patron saint of all things weird, discovered Fischer busking on the Sunset Strip. Zappa, fascinated by his rawness, signed him to his Bizarre Records label and recorded a double album, An Evening With Wild Man Fischer. The result is one of the most notorious documents in outsider music history — a sprawling, unpredictable journey through Fischer’s psyche.

Across its four sides, Fischer rants, howls, and croons through childlike ditties, stream-of-consciousness monologues, and sudden bursts of emotional breakdown. It’s the sound of a man narrating his own unraveling - unedited, and unashamed. It’s funny until it isn’t, then heartbreaking until it’s funny again. Imagine if Captain Beefheart were homeless, and you’re halfway there. Zappa preserved it all in its jagged form, letting the tape roll as Fischer bared his soul with no filter and no safety net. It really is one of the most stark outsider recordings to ever exist. And for a hot minute later, Fischer had actual, respected industry figures on his side - even opening for acts like the Byrds, Iron Butterfly, and Bo Diddley. His recordings were weird, perhaps even unlistenable to most, but had an unwieldy counterculture niche to it.

But the alliance with Zappa - and all the goodwill that came with it - didn’t last. Fischer, prone to paranoia and erratic behavior, allegedly threw a glass bottle that nearly hit Zappa’s daughter, Moon Unit. Zappa cut ties immediately, and Fischer’s brief brush with industry legitimacy evaporated. What remained was a man adrift: too unstable for the music industry, too genuine for irony, too raw for polish.

Fischer continued recording sporadically — Wildmania (1969), Pronounced Normal (1981), Nothing Scary (1984) — but never recaptured even the cult momentum of his debut. With his mental health problems going largely untreated, he spent most of the rest of his life “performing” on L.A.’s streets - a local legend to some, a bewildering curiosity to others.

The 2005 documentary “Derailroaded" captures his paradox perfectly. It’s a difficult watch — at once empathetic and exploitative, much like the world’s relationship to Fischer himself. You want to laugh, but you feel guilty doing it. You want to help, but you know you can’t. What makes Fischer’s story so tragic is that he wanted acceptance. He didn’t see himself as an “outsider” artist or a cult figure. He wanted to be famous. He wanted to be loved.

After a severe paranoid episode in 2003, Fischer was eventually institutionalized and medicated. Though this stabilized him, it also dulled his creative drive, often referred to by him as his “pep.” His final public performance occurred on August 16, 2006 in Phoenix, Arizona. He died of heart failure on June 16, 2011 at the age of 66.

If Tres & Kitsy showed that outsider music could be pure and untouched, Wild Man Fischer showed that purity can also destroy you. His songs - often tuneless, repetitive, improvised - aren’t meant to entertain so much as exorcise. Tracks like “Merry Go Round” and “Rocket Man” have a desperate joy and longing to them, a need to connect that transcends their crude, mangled form. They sound like transmissions from a man trying to make sense of a world that’s rejecting him in real time. Each song is like a scream into the void.

Fischer’s legacy today is complicated. He’s celebrated by collectors and historians as a pioneer of the outsider tradition, and to some, he’s a spiritual precursor to lo-fi, punk, and every artist who ever wore their flaws proudly. Yet he’s also a cautionary tale about how easily society romanticizes madness when it’s convenient. His art was his illness, and his illness was his art. The two were never separable. His story cuts to the heart of the conflict that shapes most outsider musicians. The very qualities that make their music so pure and singular also make them profoundly hard to work with, treat, support, or sustain in society.

If The Outsiders had a Mount Rushmore, Wild Man Fischer would be on it — not because his music is easy to love, but because it reminds us what “outsider” really means: complete creative freedom with no filter, no polish, and no safety net. Liberation and destruction rolled into one.

According to legend, Fischer once shouted to a passerby, “I’m not crazy, I’m the real thing!” He was right. And maybe that’s what makes listening to him so uncomfortable, yet so unforgettable.